Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist at Harvard University, and Maria J. Stephan . . . concluded [in their book Why Civil Resistance Works] that nonviolent movements succeed twice as often as violent uprisings. Violent movements work primarily in civil wars or in ending foreign occupations, they found. Nonviolent movements that succeed appeal to those within the power structure, especially the police and civil servants, who are cognizant of the corruption and decadence of the power elite and are willing to abandon them. And we only need one to five percent of the population actively working for the overthrow of a system, history has shown, to bring down even the most ruthless totalitarian structures.

—Chris Hedges, “Burn the Planet and Lock Up the Dissidents”

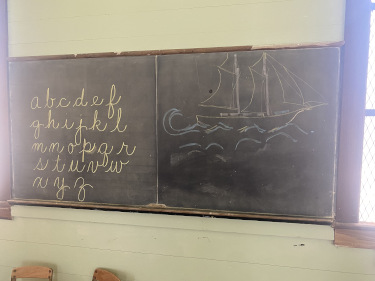

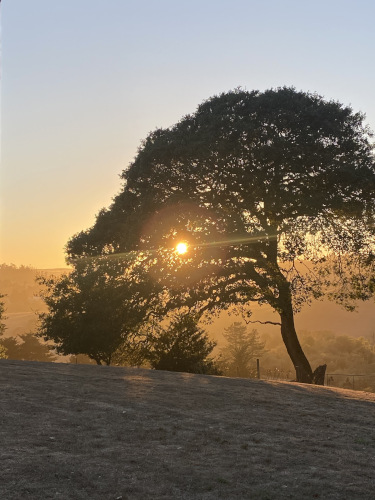

. . . We’ve all got a hill in the distance.

For some, that hill is a mountain, not a hill. But let’s all be honest: the hill in the distance might as well be a mountain for each of us, because we act like it is. We look at it, and dream about it, and think that one day it might be nice to climb it, to go see what our world looks like from there.

And then we don’t.

There are literal hills in the distance, and symbolic hills in the distance. Either way, they’re the same thing, and we don’t climb them. The hills in the distance seem too far away, and we’re certain it would anyway be quite an ascent, and who knows if there’s even a path up to it?

There is a path, though—quite a few of them. You just need to know how to look for them, and more importantly need to finally want to find them.

—Rhyd Wildermuth, “The Hill in the Distance”

Our time is the time of clocks and machines that tell us we don’t actually have time to go up into those hills. You have other things to do, the machines tell us. And we listen.

The time of those hills and those who dwell there isn’t like this. . . . But only sometimes do we hear them.

—Rhyd Wildermuth, “The Hill in the Distance”

In the form of a tiny home, a relation-ship with the Wild God is carrying these letters toward a hill across that wild blue yonder.

Things can get a bit squirrelly. In front of where I sit in a deck chair, a huge gray squirrel bounds to the birdbath for a drink, in close enough proximity that I determine he’s a he and not a she as I had thought. Occasionally pausing to peer at me, unsure of what to make of my stilled presence, he dines upon sunflower seeds I’ve scattered on the railing for chickadees, who have flitted off somewhere. I’ve discovered recently that the squirrel makes a quick BRRR sound I hear sometimes, an echo of a skunk’s similar sound at night: he thuds the railing with his hand. Is it an expression of unease—a warning—as his nerves are on alert? Is it to establish territory? To attract a mate? To drum up insects?

Respectful of the squirrel’s seeds and wondering why I’ve stopped supplying peanuts, the stellar jays perch here and there on ceanothus and redwood with hopeful expectancy, until Shrieker takes initiative to land opposite the squirrel and shriek at him. The squirrel pauses to consider it and resumes eating.

Slowwwwwly, like a living statue, I lift a peanut to the railing and deposit it there. The squirrel hesitates and resumes his meal. A jay snatches the peanut. Just as slowly, I deposit another peanut. And another.

Acorn Woodpecker arrives for a drink, followed by chickadees, who bathe as well as sip, spraying droplets in every direction.

I feel like Snow White—but where’s the witch? Oh right, I’m the witch, too.

What if the witch is not evil and is in fact in cahoots with the dwarves to draw Snow White’s prince to her? What if that union benefits everyone, crumbling the artificial hierarchy of aristocracy into alignment with the wilds?

It’s not only about changing the world. It’s about seeing the world in a different way, one that rejects the narrative of the dominant ideology. It is a re-enchantment of the world. It is about our spirit taking center stage. This is where it belonged all the time. But the spirit only becomes real through action. The spirit is made flesh, to use some old language.

—Roger Hallam from prison, via an interview quoted in Chris Hedges’ “Burn the Planet and Lock Up the Dissidents”

The boat we’re all in deposits me on the shore of a cove, where I wander around and then sit on a rock.

Gulls maintain a buffer of space between us but otherwise go about their business.

Eventually a woman and a beautiful little girl arrive. They’re quiet, but nonetheless the gulls, almost without my noticing, move out to the greater safety of the water.

In the space left by the gulls, I dip my toes in the water and then move along to my next course.

The main thing is not to hurry. Nothing good gets away.

—John Steinbeck, in a letter to his son Thom on November 10, 1958, published in Steinbeck: A Life in Letters

A new-old trail wends through coyote brush. A tree has fallen over it, forming a curtain of branches, which I wrestle out of the way. Exuberantly, a blackberry vine trails love-bites along my arm.

A bobcat emerges ahead, tail twitching, trots before me for a moment, and then disappears back into the vegetation.

I think the mainstream art world is on the wrong track. More precisely: the elite travel on the highway, but their cars fail to drive up winding mountain roads, they fail to end up getting lost in fog, or call at villages where no one stops. In those villages women spin both tales and yarn, sing blessings over herbs, carve symbols into bread, pray to rivers, deliver babies and tend the dying. . . .

Here women comb out

each other’s hair

Unravel cosmic tangles and whorls

and gently remove abandoned birds’ nests . . .

—Imelda Almqvist, “A Church of Women”

Usually when there’s a statue of some really famous person, and very often when that famous person is a saint, some spirit takes residence there. Well, with very old statues, it’s usually the other way around—there was a spirit there, and then someone builds a statue in its home.

—Rhyd Wildermuth, “The Giant by the Black Gate”

The critical reason we’re failing, in my view, is because we buy into the idea that they can oppress us by sending us to prison. While in fact, power resides in our fear of going to prison, not the act of doing it in itself. Once we realize it’s all about fear, we have that lightbulb moment. It’s not what they do to us, it’s how we choose to react that determines their power. . . .

You carry out the good, not to create good outcomes, but because it is good, because it’s truthful, because it’s a beautiful thing to do, because it creates a metaphysical harmony, a balance.

—Roger Hallam, in Chris Hedges’ “Burn the Planet and Lock Up the Dissidents”

Somehow, after my journeying, I arrive at my aunt and uncle’s place. My parents and cousins are here. Despite being ill at ease where dark walls and doors and religion close in, shutting out everything that makes sense to me, I settle in for a visit. Even with all our differences and my bewilderment, I do love these people.

As we chat, my aunt, glancing out the window, spots a gopher pushing dirt up onto the lawn. Without considering how the lawn feels about it, my uncle grabs a BB gun.

Gopher, watch out! I warn.

When my uncle returns, I don’t inquire as to the outcome and he doesn’t volunteer it, which probably means the gopher lives on.

Ravens in the distance discuss the happening in great detail. To them, just in case, I convey: If the gopher is dead, either let the body be or avoid the small lead balls in it.

When the banners of the world tremble

Stoutly in the good, clean breeze

When we come to it

When we let the rifles fall from our shoulders

—Maya Angelou, “A Brave and Startling Truth”

Just before dinner, my dad cuts up a watermelon. Perhaps because the watermelon received no warning, the long blade skitters and slips, threatening my dad’s already scarred fingers and the hair-trigger of his temper.

As I flee with anxiety, my aunt says, “You’re not supposed to run away from stressors.”

“It’s one thing if there’s something I can do about it, but there’s no reason to stand around helplessly and be stressed.”

The next day, my dad and uncle use a soundscape-shatterer to tighten screws on the deck outside my window, where St. Murph the Cat once hung out: BRR-BRR! BRR-BRR!—orders of magnitude louder than squirrel-thumps. I clear out the room for another aunt soon to arrive, and move to the treehouse, which is much more my style.

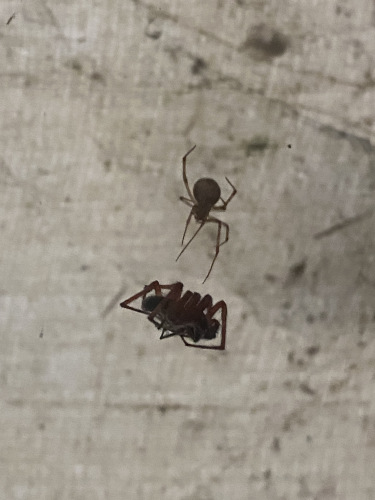

Inside the door, emerging from among old tunnel webbing and molted exoskeletons, my dear friend Hacklemesh Weaver waves a greeting.

She shows me a glorious spangle of egg sacs.

In case she has forgotten, I assure her, You and your beautiful creations are safe from my clumsy movements as long as you stick to your usual nooks and crannies.

That’s a relief. You are so big, and I am so small.

Are you eating enough?

I’m doing okay but would like more.

More is likely. All the openings and closings of doors and windows that have been jarring your soundscape create ways for your creatures of air to come in . . . or would you like to go out?

Out? Oh hmm, I don’t think so. I feel safe in here.

In the morning, though, as I lean over the sink in the big house, who should emerge from somewhere in my clothes but Ms. Weaver! “Ah!” I exclaim. You did decide to move out! You are very brave! I’m glad you survived the journey!

Because she is docile—in the way of her kind—I bring her to the living room for everyone to admire. Fortunately my cousin’s wife, who suffers from arachnophobia, is still in bed.

Then I carry Ms. Weaver out to the deck. I think you will love it under here.

She pauses and then creeps off my hand and down a gap between boards to a new life.

Even one spider expedition or black-bird call, or the arch of trees leaning over the road on my way to and from work, is enough to strengthen me.

I saw the debris from when the river flooded its banks just a few days ago. Among the garbage and silt I saw one stand of river cane, or canebrake, which had survived unscathed. . . . The canebrake stood, almost as if saying, “We expected this, we were built for this. When the river surged we bent that we would not resist the fast-moving waters. We entangled our roots to hold on to each other. This will also happen again.”

—Enrique Alberto Gómez, “Lessons of the Canebreak: A Dispatch from North Carolina”

They remind me that they’ll be there on the other side.

After I return from work to my aunt and uncle’s house, the network news comes on: bombings and political strife. My spirit retracts again. A friend sends a self-care reminder and I ask myself, Why am I watching this? I beg off for a shower and feel better.

Not that I’m imbibing tonight, but at times like these I understand the necessary medicine of alcohol: in the right doses, at the right times, it smooths over agitation and channels deeper truths.

Of course any medicine can be poison if misused; we all know the kinds of things that can happen, how we can act in defiance of, rather than for the benefit of, our day-to-day selves. The best we can do is respect it and know ourselves: our limitations, our strengths, and what we must eventually face, however unbearable.

Everyone knows on some level that our edifices stand on shifting forces and is handling it, consciously or subconsciously, from different recourses: from silent retreats to soundscape-shatterers.

Respect the naturalangsamkeit which hardens the ruby in a million years, and works in duration, in which Alps and Andes come and go as rainbows. . . . Let us approach our friend with an audacious trust in the truth of his heart, in the breadth, impossible to be overturned, of his foundations.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

The greater forces themselves are rooted in deeper meaning.

What we cannot bear as we are, where we are, eventually transforms and transports us.

Bashfulness and apathy are a tough husk in which a delicate organization is protected from premature ripening.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

So even though this piano has been lovingly refurbed, it’s incredibly old, and she says, “Amanda, your piano is coming right along. She’s very quirky, and needed some major tender loving care. Glue, clamp, rest overnight, glue in other areas, so the difference may not feel significant yet.”

Oh, this is just like reading a poem. “She has some limitations due to the way she was rebuilt.” Is that hitting hard for anyone today?

“But I have high hopes. I’ll be back in the near future. Thanks for trusting me with your instrument, and I hope to see you again soon.”

—Amanda Palmer, “She Has Some Limitations Due to the Way She Was Rebuilt”

I haven’t felt this kind of joy in many, many, many years, and I haven’t felt this safe and loved. I’ve been living in survival-mode and trauma-triage for so long that I forget that moments of pure joy are possible.

—Amanda Palmer, “‘Coin-Operated Boy’ Live at Fenway Park and a Soppy Love Note to My Boyfriend.”

And I like you because

When I am feeling sad

You don’t always cheer me up right away

Sometimes it is better to be sad

You can’t stand the others being so googly and gaggly every single minute

You want to think about things

It takes time

I like you because if I am mad at you

Then you are mad at me too

It’s awful when the other person isn’t

I like you because

I don’t know why but

Everything that happens

Is nicer with you

I can’t remember when I didn’t like you

It must have been lonesome then

I would go on choosing you

And you would go on choosing me

Over and over again

—Sandol Stoddard Warburg, I Like You

Wait, and thy heart shall speak. Wait until the necessary and everlasting overpowers you . . . .

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

There is a way to develop and nurture interdependence and trust, to cultivate vulnerable and intentional relationships between everyone involved, to be honest about when it’s hard and to move through those feelings with care, with help, with community, with internal work, with therapy, with love.

—Clementine Morrigan, Love Without Emergency

Love is not something I earn by being “good,” love is not something always under threat by outside forces. Love is freely given, loyal, kind. Love is generous, patient, steady. Love is trustworthy. . . .

When my partner is in a bad mood, distant, busy, or distracted, they still love me and it is not an emergency. When my partner is away traveling and I haven’t seen them for awhile, they still love me and it is not an emergency. . . .

I can’t even explain the pleasure of safety, the way my very bones sing with it. Learning to move through conflict with my partner, learning to move through my nervous system and return to my window of tolerance, finding myself in safety breathing against my partner’s body: there is nothing more beautiful than this.

—Clementine Morrigan, Love Without Emergency

We know all about excitement. We know all about danger. We know all about fighting for the recognition that the ways we love are legitimate. . . . But we don’t have a lot of space to talk about the staggering beauty of learning to feel safe.

—Clementine Morrigan, Love Without Emergency

When they are real, they are not glass threads or frost-work, but the solidest thing we know.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

The gems within family visits are worth the pressure. I feed my aunt’s cats and enjoy home-cooked food, amuse my dad with tales of solo dance parties and antics with critters and peanuts and sunflower seeds, and teach my mom about her first smartphone, to her exclamations of delight.

I am appreciating the little, gentle things. Close friends. Good food. A kitchen of my own.

—Amanda Palmer, “She Has Some Limitations Due to the Way She Was Rebuilt”

In my moments alone—like when the moms are making breakfast and the dads are talking guns and tools and cars—I seek out my wider sources of stability, alternately listening to trees, staring into space, resting with eyes closed, and conversing with kindred spirits in my phone.

All friendships of any length are based on a continued, mutual forgiveness.

—David Whyte, Consolations

Charles Eisenstein posts a video of a woman sharing about “everyday ministers” who unknowingly saved her from suicide. How grateful I am for all the people—including those with fur or feathers or leaves or many legs or mycelium—who have saved me time and again.

Divorced in his trailer, raising three daughters, diabetic, a recent amputee, he is an abjectly powerless person—as the political mind calculates importance. He is someone who may be moved and shaken by world events, but he is not a mover or a shaker.

I bet that some part of you knows that calculation is wrong.

There are hidden angels among us. They hold the world together. Their words and actions radiate out into society, even into politics, through utterly mysterious paths.

This man did not calculate that his kind, jocular words to Allison were his highest-leverage, impact-maximizing use of his resources. . . . He isn’t trying to figure out how to have a positive effect on the world. He doesn’t have to.

There are many like him out there. They are usually to be found in the most humble stations. You probably have met a few, now and then.

. . . They do not require anything from us, but we can amplify their work immensely through the power of gratitude and awe. These emotions open a channel . . . which enters in and sets the stage for our own transition into a higher level of service by bringing down the obstacle of self-importance. That’s a key obstacle, because most of the things that need doing today, desperately need doing, will not accrue to the doer any kind of public recognition, reward, or credit. They will not usually seem “important” to the recognition of the political mind or the save-the-world mind. And when the “important” choice does arise—whether to press the launch button, perhaps—it is thousands of “unimportant” choices that create the template for what that choice will be.

Thank you to the great souls in humble stations holding our world together.

—Charles Eistenstein, “The Man Without a Leg—A Medicine Story”

Let your greatness educate the crude and cold companion. If he is unequal, he will presently pass away. . . . True love cannot be unrequited.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

It never troubles the sun that some of his rays fall wide and vain into ungrateful space, and only a small part on the reflecting planet.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

Be gentle. Remind yourself that you are a human being having a human experience. You are not a failure or a problem. Many have walked this path before you and found solutions that work.

—Clementine Morrigan, Trauma-Informed Polyamory

After the domesticity of the family visit, my path leads me, organic kombucha in hand, right back to the wild relation-ship.

For five months I lived and worked outside, witnessing every sunrise and sunset, bathing in the cold mountain streams and observing wildlife everywhere I looked. I learned that it doesn’t take long to feel completely at home in the wilderness, because nature is our natural habitat.

—Corby Hines, in Wildlands Conservancy interview “Meet Corby Hines: The New Ranger Leading Adventures at Jenner Headlands Preserve”

The temperature cools and a faint breeze picks up, gently caressing, as if the Green Man has cracked open a door.

Here in Greenland the giggles often become so uncontrollable that they morph into hiccups and loud shrieks. Outside our windows the arctic winds respond, vociferously, to the high spirits and creative chaos energies. I hear the voices of spirit children tinkle in the growl of the Wolf Winds.

—Imelda Almqvist, “A Church of Women”

Music is the flashlight. I’m in the cave, but I see a shape, a path, a way out.

—Amanda Palmer, “The Cure, quickie shots from the tiny NYC show, and rescheduling Tarrytown & Fairfield”

Redwood drops a frond on my stomach, followed by a flurry. I spill kombucha—an inadvertent libation—and then lie down for one of my music meditations: a still, supine version of a solo dance party. The music, on shuffle, speaks to me, flows through me, putting me in touch with an aspect of myself who is not jaded or dispirited by suffering but instead knows pure innocence that somehow also encompasses and transcends the suffering.

It’s the part of me who still believes in true love and who sees how the degree of suffering entails a degree of joy that I can’t access when I’m embroiled.

Humans stalked by gods and seduced by spirits—what we call “mystery” in religion is not much different from the mystery of sex. It cannot happen alone, and the call is also an answer. We go looking for those gates, and then find out we were being led there. Like picking up the phone to call a friend and finding them already on the line before you dial, the candles we light are not our prayers, but rather our responses.

—Rhyd Wildermuth, “Finding the Gates”

Ravens draw near and strongly suggest that I bring them walnuts, but I make them wait. There’s a time for them and a time for me.

Later that day, after we’d found our way to the competition venue, one of my other Future Farmers teammates said, “She wanted to kiss you.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I think I was imagining things.”

“I saw it,” he said. “It was fire.”

—Sherman Alexie, “The Heartbreak of Horses”

I slip through the door.

* * *

I could not return. The Netherlands of my childhood doesn’t exist any longer.

—Imelda Almqvist, “Can We Ever Return?”

I emerge through the mirror at my own altar to the Wild God—at the Tenterraces.

Dazed, I stare back into the mirror at my own reflection and at the greens of the woods all around, aware—as ever in this place—of the Green Man’s eyes upon me.

becoming jaguar is to abandon the certainties of domestic life and step into a forest of gazes

—Küpa (@kupaye@zirk.us) on Mastodon

I stumble to my outdoor living-room chair, which used to be my grandfather’s, and his mother’s before him, and collapse into it. The familiar magic of the place ripples through me like music.

The raven pair arrives, excited. How did they know I’m here? It seems I came to feed them after all.

I rise and go to the ammo can in which I keep their walnuts, scoop a handful, and trek up the East-That-Feels-Like-West Trail to the Raven Log, along whose mossy length I distribute the nuts.

Upon resettling in Pa’s Chair, I suddenly sit up, as it dawns on me: the Tenterraces are, indeed, a sort of mirror image of the place, a few miles away, from which I just came. When not traveling by mirror, I climb up a hill to reach the Tenterraces, which look upon a South-facing slope across the unseen river below. For the tiny home, I go down a hillside trail and look upon a North-facing slope across an unseen creek. On a certain level of reality, are they each other’s Hill? Is this how all hills, in fact, embody the essence of one Hill?

They also feel what I feel, that these mountains are the cradle of some deep and ineffable magic.

—Libby Rodenbough, via an interview quoted in “Musicians Pull Together Massive Compilation for Western North Carolina Flood Relief”

Seemingly nothing has changed, except that I see how North and South—and East and West, and Up and Down—switch places, or are the same thing. In their whirling dance, everything is transformed.

All things come into being by conflict of opposites, and the whole flows like a stream.

—Diogenes Laërtius in Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, summarizing Heraclitus’s philosophy

What seemed impossible is not only possible but has been going on all along.

I am not interested in the bravery it takes to assert proudly that God has sent you. I am interested in the ragged bravery it takes to admit to yourself that you could be wrong, you might not understand the story. . . .

I ask that we look not at the martyr on the pyre or the valorous hero on horseback, but the shivering girl in the cell, awaiting her death by fire, and realizing that her council of divine aid were not, in fact, sending aid.

. . . Our counsel will not be heavenly, but earthly. It is our actual web of animals, fungi, insects, trees, invasive species, geological formations. And unlike abstract angels, these beings will actually show up if we show up for them—as our friends, our medicine, our food, our shelter. . . .

There will be no savior for any one of us. No personal salvation. No single person or species is going to make it alone. We need counsels of beings. Many different perspectives.

No one is coming to save us. Everyone is coming to save everyone.

—Sophie Strand, “No Savior”

Heeding the counsel of Rock Rose, I repot her. She will someday outgrow the new pot, too, and then what will I do? She’ll need to be planted in the ground then—or be too big to move—but I only rent.

Will I be in a place where I can put down roots, or will I be buried at sea?

For now I’ll just keep creeping along toward my high-flying dreams.

The ravens, having fed, swoop overhead and then perch behind me, in the direction of their log. After assessing me from there for a moment, they come around front. The one called Earth-Shaker-and-Dream-Mover (whose name I learned in a dream) alights upon a tan oak’s branch directly in front of me, and her partner settles a little way off.

“We would like more walnuts,” she says in their language.

“I already gave you your walnuts for the day,” I reply in kind, with a smile.

“Nevertheless.”

I consider it and then give in. How could I resist on such an occasion?

The moment we indulge our affections, the earth is metamorphosed . . . nothing fills the proceeding eternity but the forms all radiant of beloved persons. Let the soul be assured that somewhere in the universe it should rejoin its friend, and it would be content and cheerful alone for a thousand years.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures

It’s probably a good thing I work at a bookshop, to stay in practice with the basics of my culture’s politesse. I could become fluent in Raven and forget some of the finer points of my own species’ social language.

Then again, anyone who truly cares about me will still care even if I become a blithering social idiot.

I listen to music and dance a bit as the Moon emerges through a burst of rainclouds.

As Night—Great Mother Raven—covers me with feathers of pensiveness and peace, I snuggle into my sleeping bag. Cave Cricket (who doesn’t chirp) scritches and patters percussion on the tent material as the other crickets sing me to sleep.

In the night, I’m awakened by a medium-size critter, probably Fox or Raccoon, and a smallish critter, probably Wood Rat, who climbs on (or chews?—hard to tell as I come to) the tent and whom I deter with a loud thump.

Then comes a large critter, crashing through the undergrowth.

They sniff at my tent and whuff.

Black bear? Large dog?

I whuff back.

They withdraw, pause, and crash away. After a moment, a windchime in the empty—or maybe not?—site that way jingles.

Eventually quiet raindrops, echoing the cave cricket, soothe me back to sleep.

* * *

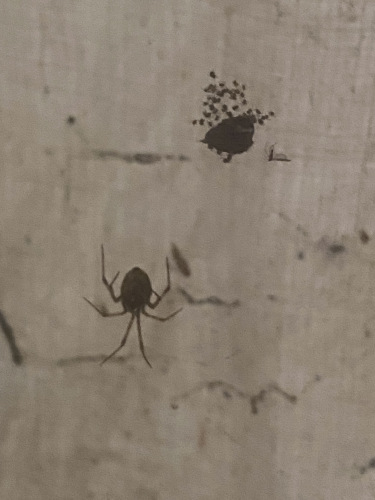

Day dawns fog-drippy and aromatic with the calls of jays, crows, and ravens. Six big itchy spots have developed around my waist and upper legs, three on each side—maybe bites from a big hacklemesh weaver who crept into crevices of my sarong without detection. These weavers huddle in “safe” places and then panic when inadvertently squashed.

Or maybe it was a huge garden-spider in the shower enclosure—whose web I inadvertently destroyed when I showered yesterday. I relocated her but might have been bitten before noticing her. Now she’s spun a web across the whole “bathroom” opening, leaving only enough space through which I can duck to the toilet bucket. I’ll climb over the inverted horse-trough from there when I’m ready to shower again, so as to respect her work.

I’m reminded of the sangoma John Lockley, whose initiation included boils on his legs. Maybe I’m experiencing some kind of initiation, too.

Each new story issues from the last.

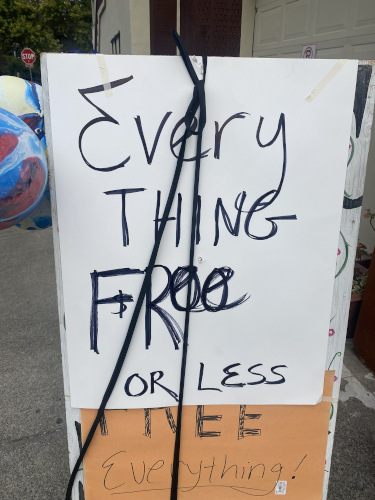

badge is free from Andy Carolan.

badge is free from Andy Carolan.