Sometimes we take dead-end roads on purpose.

I am so glad to have lighthouses all around me as I row row row this boat in the dark dark dark.

—Amanda Palmer, “Love from the road.”

We waited for the curfew to end. But the weeks passed and the curfew stayed the same. At night there was stillness where there had been the rush of traffic in town, the odd shout, or the babbling of idle boys in the streets. Barking dogs and the honk and cackle of herons in our trees replaced the human noises.

—Paul Theroux, Sunrise with Seamonsters

We pick morsels from the bones of those who picked morsels before, and offer morsels in turn.

There exists no Mother Goddess or Love Goddess who is not a Death Goddess as well. The giving of Life needs balancing by the taking or reabsorbing of Life (Death).

—Imelda Almqvist, “Of Trauma Held in Land”

Who are the morsel-picking “we,” though? I understand frolicking with you. This I get. I lose the plot when it comes to things like going around and around in cirlces, typing numbers so I can pay the bills so I can type more numbers and maybe wander the wilds sometimes. Does it do any good?

Someone holds your wrists behind your back, pushes your head down so that you must look at the floor, which is wood, beneath which is dirt, and beneath that, stone: and farther still, beneath every road, every path, there is fire.

—Maryse Meijer, The Seventh Mansion

When people succumb to violence they are filled with trauma and often a desire for revenge. The skills people need to become responsible are not taught by violence. I believe that if we rely on violence to change the world we will unfortunately just end up with more violence.

—Clementine Morrigan, “Destroying Things”

I enjoy doing good work if my heart is in it, but most of the options out there are harmful, as far as I can tell.

“Once there was no trouble here,” a man told me as we clattered across the plain. “There was no water, no trees. Only small villages. Then a dam was built and water came to the valley in a stream, and since then there has been constant fighting.”

—Paul Theroux, Sunrise with Seamonsters

Most of the options out there make me want to break things.

It is no measure of security to constantly oversee a captive population, a powder keg of resentment always on the brink of exploding in hopeless rage. Unrelenting vigilance is not true security. True security is neighborliness, good relations, ease.

—Charles Eisenstein, “How to Heal the Wound of Gaza”

When I do rune readings, at least, sometimes people hug me. Sometimes tears flow—mine included.

“I don’t want to leave. You’re going to have to come pry me off your couch!” I stared at him, daring him to actually do it, wondering how the therapist who’d never touched me to date would pull it off.

M turned aside and removed a plate of trinkets from a nearby bookshelf. He held the plate out to me and invited me to choose something to take home with me.

“Having a transitional object can help us remember our safe place,” he told me.

At that point my focus shifted to the items on the plate. I chose a small smooth turquoise and brown stone.

And suddenly I could get up and leave, and feel good about it. . . .

What I most remember and treasure about the experience was the way M treated me with dignity and respect even though as far as it looked I was “misbehaving” in a rather immature way.

I think about this a lot. In that moment M extended to me grace, and it’s something I had longed to experience for my entire life.

Amazing grace, so healing and life saving.

—Fernanda Powers, in answer to the Quora question “What would therapists do if their client refused to leave their office when their time is up?”

Somewhere nearby, a chainsaw screams, and continues screaming. Humans move to the beauty of the woods and then never run out of trees to want out of the way.

I think chronic pain (psychological and physical) stitches us to the white-hot present moment in a way that radically exceeds our ideas of good or bad medicine. There is no boat to bring you through the dark ocean of your anguished body . . . but your body itself. Storm and vessel are the same. Present and future drop away from that agonizing 1/8th of a second that is the human instant. Over many years of experiencing a spectrum of symptoms and physical breakdowns, I’ve come to believe that pain—even very intense pain—is manageable if you know it will end. But for those with incurable or terminal conditions, you don’t know if it will end. Instead, chronic pain becomes the uncanny syntax of a new grammar. One without nouns or pronouns. One without selves. It’s a language of verb, verb, verb. Now, now, now. You can only bear it one moment at a time. To project forward into a future of uncertainty is impossible.

I’ve done plenty of meditation and I’ve experimented with psychedelics. I do think they are helpful tools. Absolutely. But I have never come close to the sheer drop-off, the cliff dive, of extended physical (and mental) illness with them. My greatest mindfulness teacher is not a human being or sacred text or therapeutic model. It has been my own nausea, the tides of which have repeatedly washed away any contours of a self I thought were stable. My greatest psychedelic trips have happened totally sober, stitched by the needle of my own ailing body into the present moment again and again without recourse to memory or fantasy. . . .

I love you all. I love you who take the trips you don’t want to go on.

—Sophie Strand, “Chronic Pain Is Psychedelic”

Another machine whines like an omnipresent mosquito in all the forest’s ears, followed by a woodchipper’s fresh onslaught of guttural, reverberating agony.

I never took a moral position against killing animals for food. I was a tiny philosopher and I explained to my parents like it was obvious (because it is) that raising animals in captivity, never letting them run and play, reducing their lives to the “production” of “meat” or “dairy,” is nothing at all like a predator animal killing a prey animal. The prey animal being chased by the predator lives a free life of their own. They are not defined as “meat” or “dairy” but exist as an animal before they are killed. Importantly and significantly, they have the right to run and to use all of their evolutionarily developed skills to evade the predator. Their fate is not sealed.

—Clementine Morrigan, “Animal Agriculture and Collective Dissociation”

One time when I was a kid, I caught a neighbor kid trying to drown our cat, Dusty—who had a hernia—in our kiddie pool. His hernia swelled to the point of bursting and deepened to an angry purple. It was one of my earliest experiences of helpless rage.

There’s a greater integrity to making art that’s filled with anger and rage. There’s a greater integrity in being the artist who does that, than the artist who sublimates their anger and their rage when it shows up asking to be put on the canvas, and instead allows that rage to come out at the grocery store, or to come out directed at their partner, or their kid, or their student, or their boss, or their staff, or wherever the rage winds up landing if it doesn’t get released onto the page, or the song, or the dance.

—Amanda Palmer, “Ground control at the Fucking Earth airport”

Imbalance comes out at human and other-animal companions and trees and other wildlife and denizens of the edge who could have—would have—channeled it, soothed it, if given half a chance.

When a tree is cut down in the forest, other trees reach out to the victim with their root tips, and send lifesaving sustenance, water, sugar, and other nutrients via the mycelium. This continuous IV drip from neighboring trees can keep this stump alive for decades, and even centuries. And they don’t only do it for their own kind. They do it for the trees of other species. Why? Is it because they know that their lives depend on the health of the whole forest, and even on beings very different from themselves?

—Neil DeGrasse Tyson

Helpless rage comes out as crushing depression or wild risktaking, because what have you got to lose?

I feel that, in my art bones, you cannot turn away from what wants to be expressed.

—Amanda Palmer, “Recovery & Reconciliation, Part 57”

The only thing that helps is to claim the deep, abiding power that says, This wire of violence that tortures me ends with me.

You do not seek to punish. Rarely does anyone cease hostilities because someone has convinced him that his cause is not justified. It is hard to convince someone they are wrong. It is much easier to appeal to the part of them that, right or wrong, does not want to harm another. . . .

We have to appeal to something beyond reason. We have to appeal to the revulsion that says, “I don’t care if the slaughter is justified, it has to stop anyway!” What does a child bleeding under the rubble know of justifications? . . .

It takes huge courage to defy the mob. One who does so risks being the next victim of its fury. Well, courage literally means a capacity of heart. Certainly there are those so suffused with hatred that their hearts have no capacity anymore for compassion. Some of them are in positions of leadership in the world. To the extent their hearts are closed, they may only respond to pressure, self-interest, and force. But most people, even among the political class, have enough heart capacity that they are capable of compassion.

That is where hope lies. . . .

Some may say that only the victims of violence—not an outside observer like myself—have the right to disavow vengeance. What moved me to write this essay, though, was just that, an account I read somewhere of a Palestinian man in Gaza who was dying from injuries he sustained in Israeli captivity. Most of his family had been killed as well. Nonetheless, he said, “I forgive Israel. I forgive those who have done this.” Maybe he understood that there is a higher kind of justice than punishment or vengeance, a higher kind of justice than righting past wrongs. It is to prevent future wrongs, not just to one’s own people but to all people. If that can be achieved, then none of the victims of this horrible war will have died in vain.

—Charles Eisenstein, “How to Heal the Wound of Gaza”

My mom calls, worried because I’ve been heavy on her mind. Maybe she’s thinking about recent mountain-lion activity in my area; she doesn’t mention it but asks if I’m at my friend’s tiny home (which I am) rather than at my open-ended tent.

The red rope between the mother and her baby is the hope of our nation. It pulls, it sings, it snags, it feeds and holds. How it holds. The shock of throwing yourself to the end of that rope has brought many a wild young woman up short, slammed her down, left her dusting herself off, outraged and tender.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

I steel myself and plunge. “I think I know why you’ve been feeling me strongly. I just saw the movie Into the Wild—I don’t know if you’ve seen it. It reminded me that I also don’t fit into normal society—which is fine, but I also need to feel accepted for how I am.”

“I understand,” she says, but she doesn’t.

Through tears now, I tell her, “My biggest struggle is with you and Dad, because there’s so much about my life that I can’t talk about with you. I’m glad with how far we’ve come, but talking to you usually makes me feel drained and depleted.”

“That’s not good.” She sounds surprised and concerned.

“My life is good overall, and my friends are supportive, so I’m not at death’s door or anything like that . . . but sometimes I wonder.” Sometimes I think Mountain Lion might be my way out.

“We have a long way to go,” she says, “but we’ll get there.”

“I hope so.”

“I’m glad you shared.”

It feels like a breakthrough.

Accepting that no matter what we believe is right for them, some people will burn themselves, smoke crack, have unprotected sex, or love people who beat them can make even the most anarchist among us feel ill-at-ease. As a graduate student of mine once confessed to me, harm reduction feels like “giving up on a person.”

But harm reduction isn’t giving up on a person. It’s giving up on our fantasy of who people should be, and our illusion of controlling their fate. Harm reduction allows us to accept human beings as they truly are so that we might love them more fully. It’s humbling, and it often means sitting with grief. . . .

Most healthcare institutions will resort to physical force, restraint, drugs, guilt, theft of personal property, forced nudity, and denial of privacy in the pursuit of prolonging a life. This despite the heaps of scientific evidence showing involuntary hospitalization increases distress and the desire for suicide. Being held in a psychiatric institution has been shown to raise a person’s risk of suicide by 100 fold—including among patients who weren’t suicidal before they got locked up. That’s largely because of the trauma of losing one’s freedom.

Suicidal intention is at its root a longing for escape—and you don’t ease that longing by giving a person more to escape from.

—Devon Price, “Supporting the Suicidal No Matter What”

The mountain lion will not hurt you; they will be curious but respectful and a little fearful, and you can reach an understanding, no problem.

—A woman at a farmers market who had befriended a mountain lion and two rattlesnakes

As I write, a moment arises with a chipmunk. Normally these days I run them off if they come close in search of peanuts and sunflower seeds, as they can become demanding; I drew the line when one accidentally bit my peanut-shaped fingertip. (I’ll still occasionally lob them peanuts at a distance.) Just now, a chipmunk inched toward me in what has become an irritating little skitter . . . stop . . . skitter . . . stop cadence. I issue my usual warning: “No!”—which tends only to give them momentary pause before they keep coming and I rise and chase them off. This time, though, during one of the pauses I turn the full force of my attention on this one and hold their gaze for a very long moment, conveying that I’m to be left alone while writing—but not to worry; I will periodically throw peanuts when the time is right for me as well as for them. We hold . . . hold . . . hold the stare, and then the chipmunk turns and goes back the other way. This happens twice, and then they leave me be (until next time).

Graham wrote often about the rats that jumped and played in his hut and prevented him from sleeping—rats are villainous subsidiary characters in his book. Barbara writes, “The rats were fat and well fed, and apart from the noise they made, they left me in peace. For two or three nights they upset me and after that I grew so used to them that I ceased to notice them, and they bothered me no more.”

—Paul Theroux, Sunrise with Seamonsters

After the attempted drowning of Dusty the Cat, my parents figured out how to afford surgery for the hernia, and my brother and I still played with the neighbor kids. There were no more murder attempts: Dusty lived many more Garfield-grumpy years—until one night we heard coyotes and then never saw him again.

There’s a hidden secret in the despair paradox. Going down the depths of despair can also bring healing. . . . The more we let death—even the threats of extinction—into our souls, the more we can appreciate the current vibrant vitality of life in its many forms. And we may even be transformed by it.

—Per Espen Stoknes

Having fallen, I find peace by floating on the feelings.

The High Priestess is a card of mysteries, of silence, and of stillness, as well as the deep wisdom that comes from the body, rather than the mind. She tells us that it’s okay to sit still, to not know the answer to a problem, and to wait out storms rather than trying to stop them.

Often when troubled, worried, or anxious, or when we are facing difficult decisions and situations, we try to think our way through things. Sometimes, we might also try to take actions that not only do not help, but actually make things worse. The agency and action taught by The Magician can only get us so far; sometimes the answers we need come when we sit still, when we rest, and when we sleep.

When I see the High Priestess, I like to think of roots. They’re the part of a plant we almost never see, and they do everything in darkness. Beneath the surface, beyond what we can see, is a whole world of secrets and mysteries giving life to what is visible.

It’s okay to just let the still, silent, unseen forces in life work their magic, and to wait until we know the right course of action, the right decisions, or the right words to say. This is true even in the rare cases where The High Priestess might be pointing to the secrets of others. Again, we don’t need to know everything, nor can we, and silence is sometimes the greatest kindness we can offer each other and also ourselves.

—Rhyd Wildermuth, A People’s Guide to Tarot: A Primer for Everyone

The power of “the Eye of the Heart,” which produces insight, is vastly superior to the power of thought, which produces opinions.

—E.F. Schumacher, A Guide for the Perplexed

It’s a relief just to dream and be dreamed of.

Without the gin, at that point in my life when I was drinking more gin, I would have been majorly depressed. I accept my alcoholism. It comes and goes to varying degrees but in the end the main goal is my happiness and if alcohol helps with that, and it doesn’t make me a zombie like hard drugs, then I’m okay with it.

. . . I think it’s all good as long as you don’t hurt anybody or use your poison to justify harm to anybody. That’s why I’m good with some religious people and not with others. Like I don’t think your parents are wanting to rush off to war and conquer people. So to me, their religion is a good thing. It helps them understand the world they’re in and try to be good people in it and I have no problem with that!

—My friend Rose, in a text to me (shared with permission, as are all friends’ texts)

It’s a joy simply to swim in the drink, in salty sweetness.

No matter how restricted my world may become I cannot imagine it leaving me void of wonder. In a sense I suppose it might be called my religion. I do not ask how it came about, this creation in which we swim, but only to enjoy and appreciate it. . . .

Perhaps the most comforting thing about growing old gracefully is the increasing ability not to take things too seriously. One of the big differences between a genuine sage and a preacher is gaiety. When the sage laughs it is a belly laugh; when the preacher laughs, which is all too seldom, it is on the wrong side of the face. . . .

I want to take to the ocean of life like a fish takes to the sea.

—Henry Miller, On Turning Eighty

It can even be comforting to go under.

Passing shelter belts and fields that divide the world into squares, I always think of the chaos underneath. The signs and boundaries and markers on the surface are laid out strict, so recent that they make me remember how little time has passed since everything was high grass, taller than we stand, thicker, with no end. Beasts covered it. Birds by the million. Buffalo. If you sat still in one place they would parade past you for three days, head to head. Goose flocks blotted out the sun, their cries like great storms. Bears. No ditches. Sloughs, rivers, and over all the winds, the vast winds blowing and careening with nothing in the way to stop them—no buildings, fence lines to strum, no drive-in movie screens to bang against, not even trees.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

Things can feel more spacious beneath.

Explorations can feel richer when undertaken slowly.

It was the little everyday things that pleased me most.

—Barbara Greene, Land Benighted

. . . Wonders such as these are eternal reminders of the terrifying counter-intuitive truth that grief is not the end of things but rather the dark substrate from which great things can emerge.

—Nick Cave, “The Red Hand Files #287”

Wake, maiden among maidens

Wake up, my friend

She-Wolf, sister

who lives in the rock cave

now is the darkness of darkness itself

together we ought to ride

to the Hall of the Chosen

and to the sacred shrine

—“Song of Hyndla,” translated by Maria Kvilhaug

. . . For after that morning when I dozed in the wrecked van and awakened to the shattered window and rattling black spines of last year’s sunflowers, I have no thought for anyone but Shawnee Ray. Sometimes, falling asleep in the blowing dark, I remember how we tangled together. It was so natural, as if we grew into a single plant. And now I ache for her, now my arms are broken stems. I try to look at other women with serious and measuring anticipation, but it doesn’t work. I can’t get the feeling right.

I scold my heart for sitting turned over on the table like an empty cup. Still, I can’t accept no one else but Shawnee Ray. Even though I tell myself that love is just an image, like the mental picture of your home—which when you get back is full of anxious demands and people, far from perfect—even though I tell myself to go on from where I left off, my heart is stubborn.

. . . But the only actual evidence I have of the beautiful things that went on are mental touchstones. Room twenty-two. Twin twos.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

When the protagonist meets a woman to whom his entire being pulls him, he begins spending time with her but ultimately keeps her heart at arm’s length, too afraid to love her, telling himself that he is protecting her from his fatalistic fate, failing to recognize that love itself is that great force of self-annihilation and transformation, “rare and strange” even as the most commonplace human experience.

—Maria Popova, “How to Stop Waiting and Start Living: A Jolt from Henry James”

She rises into the popcorn air, and she begins to step free and unearthly as a spirit panther, so weightless that I think of clouds, of sun, of air above the snow light.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

I make my way out again toward a new mystery.

It will go unlike you imagine, and things will become clear at the right time, and you will do fine.

—Stephanie Culen, Duncans Mills Candle Co.

I might play around as an underwater nymph for a while.

If I sink, some glowing soul or other eventually uplifts me: a friend, a stranger, an aunt.

A great-nephew.

The Sun.

Or I’ll pull myself up to hatch.

Black fur, white stripes. The mother of all skunks. I don’t know why but I think it’s a she. . . .

There is no before, no after, no breathing or getting around the drastic moment that practically lifts me off my feet.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

Keep a hand on the frail rope. There’s a storm coming up, a blizzard.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

From such a terminal vantage point, I can communicate in new-old ways, through climbing vines and whispering grasses.

A person should not agree to work in a country that demands silence of him.

—Paul Theroux, Sunrise with Seamonsters

I croon like the sea among tumbled and rising timbers.

I sing out, Can you hear me (hear me . . . hear me)?

Are you there (there . . . there)?

Knock-knock (knock-knock-knock). Are you home (home . . . home)?

No one yet has made a list of places where the extraordinary may happen and where it may not. Still, there are indications. Among crowds, in drawing rooms, among easements and comforts and pleasures, it is seldom seen. It likes the out-of-doors. It likes the concentrating mind. It likes solitude. It is more likely to stick to the risk-taker than the ticket-taker. It isn’t that it would disparage comforts, or the set routines of the world, but that its concern is directed to another place. Its concern is the edge, and the making of a form out of the formlessness that is beyond the edge.

—Mary Oliver, Upstream

A way is built out to a mysterious outbuilding.

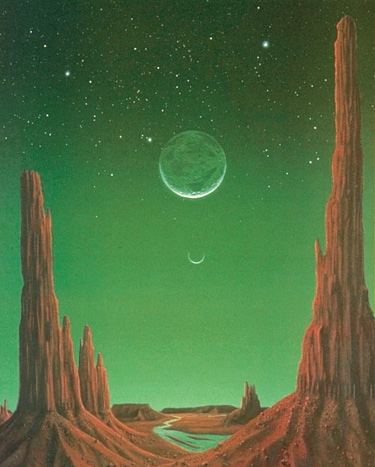

It’s a good reminder that there are whole worlds out there, awaiting me. I’ve been stuck in certain little worlds so long. It’s nice to visit other planets, get new perspectives, remember that the universe is vast.

—Amanda Palmer, “Recovery & Reconciliation, Part 57”

There’s a place to make a call, so I leave a message: I trust I’m doing something here, but I don’t know what. . . .

A call comes back.

Cometh thy soul’s voice, chanting love’s old theme,

And mine doth answer, as the pines the sea.

—Sophie Jewett, “Separation”

It’s delivered by the Earth-Shaker and Dream-Mover.

Then two enormous Ravens began circling and calling from above toward the North. They were chasing two larger birds of prey, hawk perhaps, not enormous. But bigger than Raven! It was like they were playing with them or corralling them but Raven was definitely in charge. The larger birds of prey just kept circling higher to escape their squawking. Thought of you of course.

—My friend Facet 44, in a text to me

The call is for understanding, so I stand under.

Every person alive (of any age) needs a confidante, a person they can trust absolutely and show their vulnerabilities, worries and messy pieces of self (that are a work in process). We all need people we can tell: “I messed up” without being judged or the information being used against us at some future time.

—Imelda Almqvist, “Spiritual Toolkit Work with Children”

We have a long chat.

You never know where you’re going to find your twin in the world, your double. I don’t mean in terms of looks, I’m talking about mindset. You never know where you’re going to find the same thoughts in another brain, but when it happens you know it right off, just like you were connected by a small electrical wire that suddenly glows red hot and sparks.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

We say, I love you. I find you fascinating. You are special to me.

One of us says, Thank you for the walnuts.

We flow with the music of our dreams.

I should like to rise and go

Where the golden apples grow;

—Robert Louis Stevenson, “Travel”

Our hearts rise with the song of the unicorn.

It would be in vain to try to put into words that immeasurable sense of bliss which comes over me [when] a new idea awakens in me and begins to assume a definite form.

—Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, in a letter to his patroness

Quiet warmth floods my heart.

When I feel the expansive pleasure in my heart I want to shut it down. When I feel myself melting into intimacy, that precious feeling of connection I have longed for all my life, there are parts of me that try to shut it down. My anxious and avoidant attachment strategies are two sides of the same coin, two ways to not feel what I am feeling because what I am feeling scares me. . . .

Reading those words now made me pause and reflect on how fucking far I’ve come. My problem today is that my heart keeps exploding. My problem today is that I have access to so much sensation and connection that my system is struggling to process it. In a very real way my problem is that all my dreams are coming true. My problem is that the experiences I’ve always wanted are happening to me now. And it is fucking scary to get what I’ve always wanted. It is fucking scary to be open to so much sensation and connection and transformation.

—Clementine Morrigan, “Love in Abundance Is What My Heart Was Made For”

Cheers to that.

With messages exchanged, I return from the outer edges.

As we emerged from Cathedral Grove an elderly Park Ranger approached us. “The trees talked to you, didn’t they? I can always tell from the look on people’s faces. I’ve been here a long time. When you’re around redwoods, they’ll talk to you—if you’re listening. They talk to each other and other trees too.”

—Mark Anthony, “Trees Talk—Are We Listening?”

This is the way.

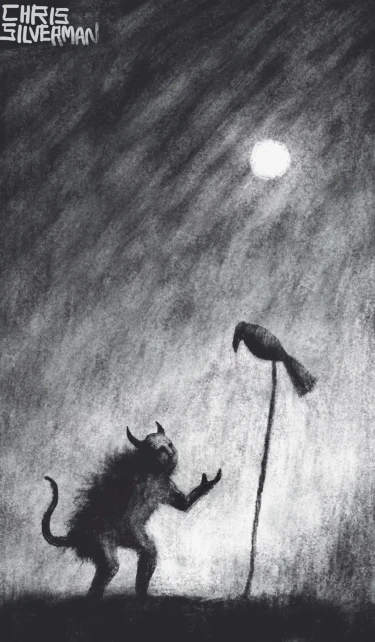

Most pre-Christian belief systems have a female figure who is a Protector of All Wild Things and also a trickster, a shapeshifter and a Mistress of Initiation. . . . She represents the freedom that fearless shadow work and wild places offer. She helps us rewild ourselves and retrieve our FERAL SELVES.

. . . She does not really eat children but she does teach that children need to pass through initiations in order to grow up.

—Imelda Almqvist, “Baba Yaga”

I feed the hungry ghost of a self past, who grows into an ally.

We can stop pretending that sliding into someone’s dms to tell them that the writer or musician they like is “bad news” does anything at all for survivors of child sexual abuse and we can begin to ask ourselves, what would actually help? We can face the reality that people we love, respect, and admire abuse children. We can face the reality that incest is not monstrous and unthinkable, but actually quite commonplace and normalized. . . .

I think we are way too comfortable asking “how could she?” as a rhetorical question, rather than as a real question. I want us to sincerely ask: how could she? What created the circumstances in which an intelligent, successful, feminist woman could tolerate knowing that her partner is a sexual threat to her children? How did that come to be? It is only when we seriously wrestle with this question that we will begin to understand how incest works, and therefore, how to prevent it. In my mother’s case I know that she grew up inside the realm of unreality where neglect, abuse, and sexual violence were commonplace and never spoken of. She has trauma stacked on top of trauma and she was taught nothing healthy about family, autonomy, sexuality, or boundaries.

—Clementine Morrigan, “What If Your Mom Is a Famous Feminist and She Didn't Protect You from Sexual Abuse?”

However broken I might be, I’ll dance with the limbs I have left.

I have woven a parachute out of everything broken . . . .

—William Stafford, “Any Time”

Upon my return, my outlook has become rather more outstanding.

Their poverty secured their freedom.

—Edward Gibbon, writing of ancient Germans

Trials never end, of course. Unhappiness and misfortune are bound to occur as long as people live, but there is a feeling now, that was not here before, and is not just on the surface of things, but penetrates all the way through: We’ve won it. It’s going to get better now. You can sort of tell these things.

—Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Don’t go

too crazy

it could get

even better

—nexus II (@vasto@mas.to on Mastodon)

Perspectives expand as new directions light up.

. . . Choosing one little lane to do our own bit of work in—literally ANY lane, so long as it is accessible and motivating to us and plays to our strengths—will mean that we are actually making a difference consistently and connecting to others who are taking part in the work too. . . .

I believe that even the concept of “activism” creates an artificial divide between ourselves as actors and the people framed as “receiving” our support, which positions us as “above” them and as sacrificing something in order to help them. It is better, I think, to view ourselves as all completely interdependent as a matter of course, and mutually so. . . .

Do not for a SECOND tell yourself that the work you are doing is worthless because it’s not tinged with suffering and danger and bodily harm. It is a Puritanical Christian myth that the only things that matter are activities that cause suffering. Suffering is not moral. Sacrifice is not moral. The impact of our actions is what matters, not how hard those actions were to do.

Some of the most impactful organizing work in the world is easy and feels pleasant, because it turns out that humans desperately crave being around one another and being able to help one another, and we miss the ability to do so in our everyday lives.

Feeding people, watching people’s kids, driving people to the hospital, letting a suicidal person crash on your couch for the night, setting up a community library, giving poor trans people your clothes, performing jail support, talking to the unhoused guy outside your apartment who is agitated—these are impactful, far-reaching actions that bring a whole lot more good into the world than having your skull split open by a cop because some self-appointed protest organizer on a megaphone told you to keep pushing back when your group was outnumbered.

—Devon Price, “When You Live Your Values Every Day, There’s No Need for Activist Guilt.”

The beauty of the system is that, while the world finds it hard to be tolerant of the non-scorer, there is always room for him in the extended family. He is “a good scout,” “loads of fun,” the comedian at family get-togethers. To ridicule a member of the family for being bone-idle was considered heresy: if we wouldn’t have him, who would? Indeed, being “a good scout” counted considerably more than splitting the atom, something I suppose our physicist uncle did every day.

But we had cousins who weren’t cousins, aunts who weren’t aunts. An extended family includes people who have been recruited because they are liked and might be useful. Growing up, I noticed how children from smaller families used to become attached to ours. They used my older brothers as I did—to find out how cars worked or to learn baseball. They ate with us and if we were going somewhere my father encouraged them to come along. . . . As time went on, they remained part of the family, acting as unpaid handymen or plumbers or lawyers or whatever. The system was subtle, but if an outsider was willing (and “a good scout”) he could find himself the object of a recruitment campaign.

—Paul Theroux, Sunrise with Seamonsters

I soon realised that I had started shedding my hyper busy and alert human “energy field” or vibe. Animals allowed me to come much closer. They were not (no longer) disturbed by my human presence.

—Imelda Almqvist, “Shedding a Human Layer to Get Closer to Animals”

I wear my heart on more than just my sleeve.

Wings of sweat, dark blue, spread across the back of his work shirt—he always wore washed-blue shirts the color of cloudy shade. His blackbird hair had grown out of its haircut and flopped over his forehead. When he stood up and turned away from the car, Shawnee Ray saw that he had a butterfly in his hands.

. . . Her father held in his toughened hands the butterfly, brittle and long dead, but still perfect. It was black and yellow-orange, all charred lines and fire. He put his hands out, told Shawnee Ray to stand still, and then, glancing once into her serious eyes, he smiled and rubbed the butterfly wings onto her collarbone and across her shoulders, down her arms, until the color and the powder of it were blended into her skin.

“Ask the butterfly,” he whispered, “for help, for grace.”

Shawnee had felt a strange lightening in her arms, in her chest, when he did this. The way he said it, she had understood everything about the butterfly. The sharp, delicate wings, the way it floated over grass, the way it seemed to breathe fanning in the sun, the wisdom of how it blended into flowers or changed into a leaf. In herself, Shawnee knew the same kind of possibilities and closed her eyes almost in shock, she was so light and powerful at that moment. Then her father caught her up and threw her high into the air. She could not remember landing in his arms or landing at all. She only remembered the last sun filling her eyes and the world tipping crazily behind her, out of sight.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

STEP 1: FIND A BEE

STEP 2: FOLLOW YOUR BEE

STEP 3: CONGRATULATIONS, YOU ARE NOW AT YOUR NEW HOME

—Heather Buchanan, Vurbo Horror Scoop, 8 July 2024

Before a move, one must rest up and prepare.

I return to my own space, curl up in Pa’s Chair with my favorite incense to deter mosquitoes, and listen to ticking cicadas and the occasional truck’s backup beeper, fortunately faint.

Love won’t be tampered with, love won’t go away. Push it to one side and it creeps to the other. Throw it in the garbage and it springs up clean. Try to root it out and it only flourishes. Love is a weed, a dandelion that you poison from your heart. The taproots wait. The seeds blow off, ticklish, into a part of the yard you didn’t spray. And one day, though you worked, though you prodded out each spiky leaf, you lift your eyes and dozens of fat golden faces bob in the grass.

. . . After I get clear of the old lady’s house, I am never quite sure about all the things that she told me, for it seems as though the important ones have entered my understanding from the inside. . . . Admit your love, I think she said, take it in although it tears you up.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

A cloud of gnats dances before me in lowering sunlight, saying something I don’t quite understand about the Many and the One.

For my love is larger than it was before she blasted it with fire. It was a single plant, a lovely pine, but now seeds, released from their cones at high temperatures, are floating everyplace and taking root on every scraped bare piece of ground. My love before she got so mad was all about what was best for Lipsha Morrissey. Since those endless moments of truth and rage in Zelda’s yard, I have reconsidered. If my love is worth anything, it will be larger than myself.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

From the middle distance, a high-pitched droning starts up, moaning as if directly into my ear—a renewed assault on all the woodland’s soundwave-sensitive parts. After a while, a human in the closer middle distance starts up music with a good drum track, ostensibly to drown it out. It does not drown it out. A jay starts up their most beautiful song. Miraculously, it drowns it out a little bit.

Care is not the end of real life, interesting life or important life. In fact, for me it was, in many ways, the beginning to my most intellectually, philosophically and spiritually demanding and inspiring life yet. The more I began to see that, and the more I let my caring self enrich my other identities, such as being a writer, a friend and a wife, the more I enjoyed it.

—Elissa Strauss, “How to Get the Most Out of Caregiving”

Though the night is young, I bed down, cocooning myself in the comfort of my sleeping bag as if in a hug.

I’d try to sleep for as long as possible, because waking up meant going back to the real world.

—Nikhil Suresh, “On Burnout, Mental Health, and Not Being Okay”

I dream of male cardinal, Bird of Peace, perched on a tall stick over a rusted oil barrel in a desert, leaning forward as though overseeing something. The feeling is of a scoured peace, as after destruction. As I watch, the cardinal turns bright yellow, becoming the Yellow Bird of Freedom and Understanding.

Dust of Snow

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

—Robert Frost, “Dust of Snow”

In the morning, I wake to a wingless fly after an extra-hard time parting from the dreamlands, which often precedes something wonderful.

Starting at 8, there’s more noise. A day of social commitments follows. Going through the motions, barely able to tolerate the tiniest irritations, I long for peace.

I groan out loud and curl into myself and for the rest of the night whenever some noise startles me I jump up, shout, and then settle back again to wait for the next advance . . . . I keep peering and staring into the faceless dark that is not even lit by the glow of wild eyes.

—Louise Erdrich, The Bingo Palace

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

—Viktor Frankl, Austrian scientist and Holocaust survivor

There is a risk in assuming the worst about how a conversation will go. What if the chat you avoid having could help resolve a problem in your relationship, or clarify an area of disagreement? What if it wouldn’t be nearly as rough as you expect? Encouragingly, research suggests that, in many cases, this sort of twist is likely. Nicholas Epley, a psychologist at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and his colleagues have repeatedly found that sit-down conversations—even ones about seemingly touchy subjects—often end up being more positive experiences than people anticipate.

—Matt Huston, “Why That Hard Conversation Will Probably Go Better Than You Think”